(Editor’s note: This blog is part of a LISC Phoenix monthly series, Communities on the Line.)

The Phoenix metropolitan area has a world-class freeway system and wide arterial streets laid out in a marvelous grid pattern to move people around and within a vast, car-dependent region. Residents can’t be happy.

Seriously. Neuropsychology, sociology and public health lessons about happiness tell us what we’ve done over 30 years to build communities and move cars in the region generally is at odds with creating environments for widespread personal satisfaction.

Urban design patterns throughout greater Phoenix discourage social connections vital to the desired human condition we call happiness or well-being, urbanist Charles Montgomery said during a recent visit. A growing body of scientific research tells us unhappiness invites social, health and economic miseries that stifle individual and community prosperity, he said.

“Cities really do make or break our well-being in their systems, through architecture, through public space,” Montgomery said. “They change how we feel, they change how we move and they change how we treat other people in ways most of us don’t even realize.”

Despite obvious challenges, Montgomery said, the good news about the region is it has tremendous opportunities to create happiness. Some examples, particularly within the Valley Metro light-rail transit corridor, already exist, he said.

Charles Montgomery, author of “Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design,” said there’s hope for the Valley’s transportation system.

The great news is that planners and local leaders have started talking about a next-generation regional transportation plan that will have a markedly different objective than the plan that produced today’s freeway system. Planners will visualize happiness in a regional transportation plan called Imagine.

Montgomery, author of Happy City: Transforming O

ur Lives through Urban Design, was the keynote speaker last month for a LISC Phoenix 25th anniversary celebration event. He also met with local elected officials, made a presentation to the Maricopa Association of Governments (MAG) Regional Council and was the featured guest at a MAG transportation planning workshop that attracted planners, engineers, developers, academics, public health experts and city officials.

At the May 24 LISC Phoenix public event on the downtown Arizona State University campus, Montgomery said the pursuit of happiness in urban design is not a warm-and-fuzzy idea. Scientists today pull from many disciplines to investigate the relationship between environmental conditions, our brains, our bodies and well-being. Happiness and satisfaction can be defined and measured in various ways, from levels of oxytocin secreted from the pituitary gland to economic impact studies.

We know that family and friends matter to the health and well-being of individuals, but research is finding out that relationships with everyone else in the city matter as well, Montgomery said. Studies show the more contact people have with strangers the happier they said they were at the end of the day. Saying “Hi” to someone during a walk to a transit station, smiling at people in a coffee shop, admiring an interesting piece of art in a public space while bicycling to work — it’s all good.

“People with strong connections to family, friends and community are more productive at work; they’re less likely to get sick; they’re more likely to recover from cancer; they’re more resilient; they live on average 15 to 17 years longer than those who are socially disconnected,” Montgomery said. “Social connections matter. Nothing matters more to well-being.”

By design, car-centric communities deny people opportunities for social connections. People who drive for their daily commutes experience more rudeness and incivility than people moving any other way. In studies and experiments, people self-report that the longer the commute the less happy they are, Montgomery said.

Geographers studying American cities say the main thing that limits people’s ability to socially connect is the degree to which we have pushed the functions of the city apart, Montgomery said. The more dispersed, the more spread out things were from each other, the less likely people were able to socialize, do business, to meet each other face to face.

It’s difficult in some communities to go to the grocery store without a car. Long commutes rob free time to spend with family and to participate in community-building activities. Busy streets discourage walks to parks, making children “prisoners of cul de sacs,” Montgomery said.

“We have a mountain of evidence to show that everything you do to build a region that’s more connected, that’s easy to get around, that gives people more opportunities to have time with family and even bump into strangers on the street — these things are not just going to make your cities more fair and more healthy; they’re not just going to lower your tax burden; they’re not just going to bring more business; they’re not just going to make your children more free; they’re going to make your own life easier and more joyful,” Montgomery said.

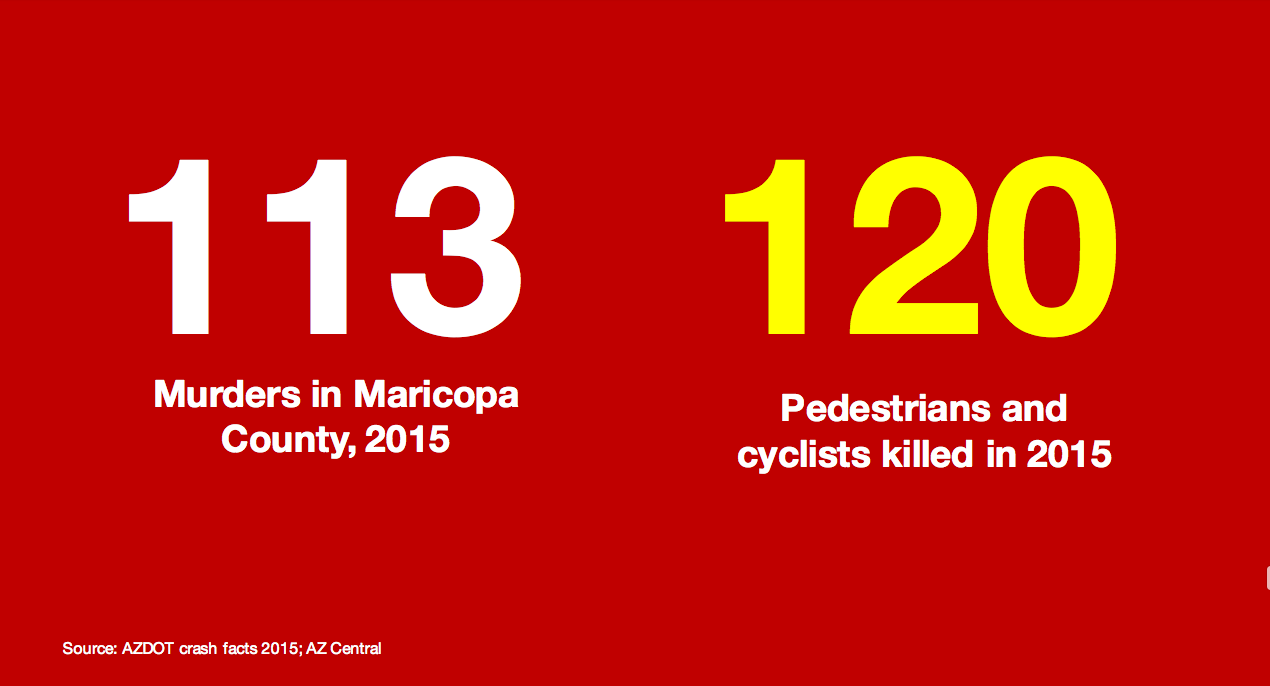

The efforts could also save lives.

One of the most startling observations Montgomery made during his visit is how dangerous it is to walk or bicycle in the Valley. In 2015, there were 113 murders in Maricopa County. That same year, 120 pedestrians and cyclists were killed.

Montgomery told attendees of the LISC Phoenix event that creating happy cities requires active participation in the processes that determine how we move about the region. MAG’s process of doing active transportation in its regional strategy is the perfect vehicle for public input.

“You’ve got to be involved,” Montgomery said. “The louder you are, the harder you push the more likely these plans are to be comprehensive and to serve everybody.”

After Montgomery’s visit, Terry Benelli, executive director of LISC Phoenix, said now is the opportunity to do things better?

“LISC Phoenix will be involved in the MAG planning process, and we hope others will join us in seizing this moment to rethink our regional transportation priorities,” Benelli said. “We hope to find partners in this critical step in building happy cities by the end of the summer.”

Audra Koester Thomas, MAG transit project manager, said Imagine will include an active transportation component that focuses on pedestrian needs in connecting to other modes of travel and to place-making sites throughout the region. The regional transportation plan will reflect the values of MAG constituents and what makes our region unique, matching infrastructure investments accordingly, she said.

“Instead of just thinking about freeways and how’s the most efficient way to get a car from here to there, we really want to focus on how we connect people, making this a place where we’ll thrive and prosper in the future,” Thomas said.

“Imagine will be informed by work including the active transportation plan, the commuter rail efforts, the transit framework program we’re putting together,” Thomas said. “It will reflect a new paradigm in how we facilitate integrated, interdisciplinary planning, where we’re focused more on our residents, our constituents and what makes this region a place where future generations want to live.”

Imagine that.